Key messages

- An anxiety disorder is a psychological condition indicated by frequent, intense and excessive worry, occurring for at least six months, and substantially affecting daily functioning and causing significant distress. It includes feeling nervous, anxious or on edge, and not being able to stop or control these feelings.

- Moderate-to-severe anxiety symptoms, an indication of an anxiety disorder, affect one in five people with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes, and one in six with type 1 diabetes or non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes; this is within the range of general population estimates.

- Elevated anxiety symptoms in people with diabetes are associated with sub-optimal diabetes self-management and metabolic outcomes, diabetes complications, depressive symptoms, and impaired quality of life and can be difficult to recognise, as severe anxiety and panic attacks share some similar physical symptoms to hypoglycaemia (e.g. sweating, increased heart rate, shaking and nausea).

- A brief questionnaire, such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Seven (GAD-7), can be used for identifying people with elevated anxiety symptoms. However, a clinical interview is needed to confirm an anxiety disorder.

- Anxiety disorders can be treated effectively (e.g. with psychological therapies and medications).

Practice points

- Assess people with diabetes for elevated anxiety symptoms using a brief validated questionnaire; remember that anxiety disorders need to be confirmed by a clinical interview.

- Treatment of an anxiety disorder will depend on severity, context and the preferences of the individual. Helping people with an anxiety disorder to access suitable treatment may require a collaborative care approach beginning with the person’s GP.

- Remain mindful that elevated anxiety symptoms also need attention, as they can develop into an anxiety disorder.

How common are elevated symptoms of anxiety?

|

|

|

|

What is an anxiety disorder?

An anxiety disorder is a psychological condition characterised by persistent and excessive anxiety and worry. This is also known as clinical anxiety. The worry is accompanied by a variety of symptoms:

- emotional (feeling uneasy, worried, irritable or panicked, including experiencing panic attacks)

- cognitive (thinking that one cannot cope, or having difficulty concentrating)

- behavioural (aggression, restlessness, fidgeting or avoidance)

- physical (a rapid heartbeat, trembling, dizziness, sweating or nausea)

In contrast to non-clinical anxiety, which is a normal response to a perceived threat or stressful situation, an anxiety disorder is problematic as it affects day-to-day functioning and causes significant distress. It cannot be attributed to the effects of a substance (e.g. medication), a medical condition (e.g. hyperthyroidism), or another mental health problem (e.g. depression).

Anxiety disorders can take many forms, including:

- generalised anxiety disorder: intense excessive and daily worries about multiple situations

- social anxiety disorder: intense excessive fear of being scrutinised by other people, resulting in avoidance of social situations

- panic disorder: recurrent, unpredictable, and severe panic attacks

- specific phobia: intense irrational fear of specific everyday objects or situations (e.g. phobia of spiders, injections, or blood).

The ‘gold standard’ for diagnosing an anxiety disorder is a standardised clinical diagnostic interview, for example the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID; www.scid5.org). Comprehensive descriptions of anxiety disorders, symptoms and diagnostic criteria are included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10). For example, generalised anxiety disorder is indicated by persistent and excessive anxiety and worry that is difficult to control, occurring more days than not, in addition to three or more of the following symptoms being present on more days than not, for at least six months:

- restlessness or feeling ‘on edge’

- being easily fatigued

- difficulty concentrating or mind going blank

- irritability

- muscle tension

- sleep disturbance (difficulty falling or staying asleep, or restless, unsatisfying sleep)

People with an anxiety disorder may experience panic attacks, which are sudden surges of intense fear. The symptoms of panic attack vary from person to person but commonly include a combination of: quickened heartbeat, heart palpitations, shortness of breath, dizziness, nausea, sweating, shaking, dry mouth, numbness sensations, hot flushes or cold chills, feelings of choking, derealisation (feelings of detachment from one’s surroundings), depersonalisation (feeling detached from oneself), and fear of ‘going crazy’, ‘losing control’, fainting, or dying.

A subthreshold anxiety disorder is characterised by the presence of elevated anxiety symptoms that do not meet the full diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder. Although less severe, such symptoms are typically persistent, can also cause significant burden and impairment, and deserve attention in clinical practice.

Anxiety disorders in people with diabetes

Diabetes is associated with both elevated anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders. There is evidence of a bi-directional association between anxiety and diabetes. Therefore, it is possible that people with elevated anxiety symptoms or an anxiety disorder may be at increased risk of developing Type 2 diabetes, while having Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes may place people at increased risk of developing elevated anxiety symptoms or an anxiety disorder.

Overall, the prevalence of elevated anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders in people with diabetes is within the range of general population estimates. Further research is needed regarding the specific types of anxiety disorders associated with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes.

Many factors may contribute to the development of elevated anxiety symptoms or an anxiety disorder. These include: personal or family history, personality, stressful life circumstances, substance use, and physical illness. Diabetes may be completely unrelated for some people, while for others, it may be a contributing factor. As various factors can contribute, the exact cause will be different for every person.

In people with diabetes, elevated anxiety symptoms are associated with adverse medical and psychological outcomes, including:

- sub-optimal self-management and unhealthy behaviours (e.g. reduced physical activity, smoking, or heavy use of alcohol)

- elevated HbA1c6 and other sub-optimal metabolic indicators (e.g. higher BMI, waist-hip ratio, waist circumference, triglycerides, or blood pressure; lower HDL cholesterol)

- increased prevalence of diabetes-related complications and co-morbidities

- the presence of depressive symptoms and impaired quality of life

People with a co-existing anxiety disorder and depressive symptoms are likely to experience greater emotional impairment and take longer to recover.

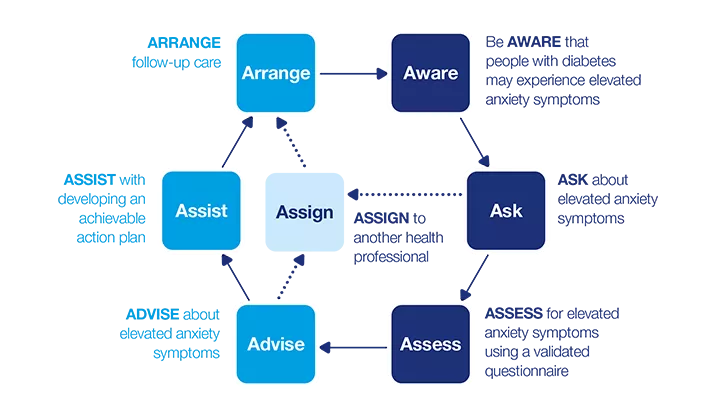

7 A’s model: Anxiety disorders

This dynamic model describes a seven-step process that can be applied in clinical practice. The model consists of two phases:

- How can I identify elevated anxiety symptoms?

- How can I support a person with elevated anxiety symptoms?

Apply the model flexibly as part of a person-centred approach to care.

How can I identify elevated anxiety symptoms?

Be AWARE

Anxiety disorders have emotional, cognitive, behavioural and physical symptoms. Some common signs to look for include: excessive and persistent worry, panic attacks, and irritability. Also, look for signs that the person is not coping, such as disturbed sleep. Each person will experience different symptoms of an anxiety disorder.

Two classification systems are commonly used for diagnosing anxiety disorders: DSM-53 and ICD-10.2 Consult these for a full list of symptoms and the specific diagnostic criteria for each type of anxiety disorder.

Anxiety symptoms may be mistaken for symptoms of hypoglycaemia (and vice versa). For example, pounding heart, confusion, shaking, sweating, dizziness, headache, and nausea are symptoms of both hypoglycaemia and panic attacks. Consequently, elevated anxiety symptoms may be overlooked or misinterpreted (e.g. as a physical health condition) by people with diabetes and health professionals, and anxiety disorders may go unidentified and undiagnosed.

ASK

- You may choose to ask about elevated anxiety symptoms:

- when the person reports symptoms or you have noted signs (e.g. changes in mood/ behaviours)

- at times when the risk of developing an anxiety disorder is higher, such as during or after stressful life events (e.g. bereavement, traumatic experience, diagnosis of life-threatening or long-term illness) or during periods of significant diabetes-related challenge or adjustment (e.g. following diagnosis of diabetes or complications, hospitalisation, or severe hypoglycaemia with loss of consciousness)

- if the individual has a history of anxiety disorder(s) or other mental health problems

- in line with clinical practice guidelines

Take the time to ASK about well-being at every consultation. It is a good way to create a supportive environment and build rapport. It may also help you gain some insight into things that may be impacting on their diabetes self-management and outcomes that may not arise through discussion specifically about the physical or medical aspects of diabetes.

There are various ways to ask about elevated anxiety symptoms. You may choose to use open-ended questions, a brief structured questionnaire, or a combination of both.

Option 1: Ask open-ended questions

The following open-ended questions can be integrated easily into a routine consultation:

-

‘I haven’t seen you for quite a while; tell me about how you have been?’

- ‘I know we’ve talked mainly about your diabetes management today but how have you been feeling lately? Tell me about how you have been feeling emotionally.’

If something during the conversation makes you think that the person may be experiencing elevated anxiety symptoms, ask more specific questions, such as:

- ‘You seem to be worrying about many different things in your life at the moment; how is this affecting you?’

- ‘You mention that you’ve been [very tired, feeling ‘on edge’/tense/stressed] lately. There’s a lot we can do to help you with this, so perhaps we could talk more about it?’

If the conversation suggests the person is experiencing elevated anxiety symptoms, further investigation is warranted.

Option 2: Use a brief questionnaire

Alternatively, you can use a brief questionnaire to ask about elevated anxiety symptoms in a systematic way. Collectively, the following two questions are referred to as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Two (GAD-2) questionnaire. They are the core symptoms required for a diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder.

You can find the GAD-2 on the full PDF version of this guide (3MB)

Instead of administering this as a questionnaire, you could integrate these questions into your conversation.

Sum the responses to the two questions to form a total score. A total score of 3 or more indicates elevated anxiety symptoms, further assessment is warranted.

At this stage, it is advisable to ask whether they have a current diagnosis of an anxiety disorder and, if so, whether and how it is being treated.

If the total score is 3 or more, and the person is not currently receiving treatment for an anxiety disorder, you might say something like, ‘You seem to be experiencing some anxiety symptoms, which can be a normal reaction to [...]. There are several effective treatment options for anxiety, but first we need to find out more about your symptoms. So, I’d like to ask you some more questions, if that’s okay with you’.

You may then decide to assess for an anxiety disorder using a more comprehensive questionnaire.

If the total score is less than 3 but you suspect a problem, consider whether the person may be experiencing diabetes distress, depression, or another mental health problem.

ASSESS

Validated questionnaire

The seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire (GAD-7) was designed to identify symptoms of generalised anxiety disorder. It is also a helpful indicator of panic attack and social anxiety. It is quick to administer and freely available online (www.phqscreeners.com). Each item is measured on a four-point scale, from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Scores are summed to form a total score ranging 0-21.

In the general population, GAD-7 scores are interpreted as follows:26

• 0-4 indicates no anxiety symptoms (or a minimal level)

• 5-9 indicates mild anxiety symptoms

• 10-21 indicates moderate-to-severe anxiety symptoms.

Asking the person to complete the GAD-7 can be a useful way to start a dialogue about anxiety symptoms and the effect they may have on the person’s life and/or diabetes management. It can also be useful for systematically monitoring anxiety symptoms (e.g. whether the symptoms are constant or changing over a period of time).

Remember that anxiety symptoms can overlap with hypoglycaemia symptoms (e.g. sweating, shaking). Therefore, take care to consider the context of somatic symptoms, as the GAD-7 items assess symptoms but cannot attribute the cause of the symptoms.

A GAD-7 total score of 10 or more must be followed by a clinical interview using DSM-53 or ICD-102 criteria to confirm an anxiety disorder.

Additional considerations

What type of anxiety disorder is it and how severe is it? If the GAD-7 indicates a possible anxiety disorder, confirm this through discussion about the symptoms and a clinical interview. For example, is it generalised anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, or panic disorder?27 It is important to consider whether the person has multiple co-morbid anxiety disorders.

What is the context of the elevated anxiety symptoms? Are there any (temporary or ongoing) life circumstances that may be underlying the elevated anxiety symptoms (e.g. a traumatic event, chronic stress, changing/loss of employment, financial concerns, or family/relationship problems)? What social support do they have? What role do diabetes-specific factors play (e.g. fear of hypoglycaemia)?

Are there any factors (psychological, physiological, or behavioural) that are co-existing or may be causing/contributing to the elevated anxiety symptoms? This may involve taking a detailed medical history, for example:

- Do they have a history (or family history) of anxiety or another psychological problem? For example, depression, past trauma, bipolar disorder, alcohol or substance abuse, or somatic symptom disorder. These conditions must also be considered and discussed where applicable (e.g. When and how was it treated? Whether they thought this treatment was effective? How long it took them to recover?).

- Is there an underlying medical cause for the symptoms? For example, hypoglycaemia; hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism; an inner ear, cardiac, or respiratory condition; vitamin B deficiency; or medication side-effects.

- Explore other potential contributors. For example, what medications (including any complementary therapies) are they currently using? Do they use illicit drugs and/or consume alcohol?

Is this person at risk of suicide? See Box 6.3 for information about suicide risk assessment.

No elevated anxiety symptoms – what else might be going on? If the person’s responses to the questionnaire do not indicate the presence of elevated anxiety symptoms:

- they may be reluctant to open up or may feel uncomfortable disclosing to you that they are anxious

- consider whether the person may be experiencing another psychological problem (e.g. diabetes distress, depression, or a diabetes-specific fear.

If any of these assessments are outside your expertise, you need to refer the person to another health professional.

How can I support a person with elevated anxiety symptoms?

ADVISE

Now that you have identified that the person is experiencing elevated anxiety symptoms, you can advise them on the options for next steps and then, together, decide what to do next.

- Explain that their responses to the GAD-7 indicate they are experiencing elevated anxiety symptoms, and also that they may have an anxiety disorder, which will need to be confirmed with a clinical interview and that anxiety symptoms fluctuate dependent on life stressors and that it may be necessary to reassess later (e.g. once the stressor has passed or is less intense).

- Elicit feedback from the person about their score (i.e. whether the score represents their current mood).

- Explain what an anxiety disorder is, and how it might impact on their life overall, as well as on their diabetes management.

- Advise that anxiety disorders are common and that help and support are available; anxiety disorders are treatable and can be managed effectively.

- Recognise that identification and advice alone are not enough; explain that treatment will be necessary and can help to improve their life overall, as well as their diabetes management.

- Offer the person opportunities to ask questions.

- Make a joint plan about the ‘next steps’ (e.g. what needs to be achieved to reduce anxiety symptoms and the support they may need).If the person confirms elevated anxiety symptoms in recent weeks, explore whether it is related to a specific temporary stressor (such as public speaking) or a continuous stress (such as ongoing work or financial problems), as this will help to inform the action plan.

Next steps: ASSIST or ASSIGN?

The decision about whether you support the person yourself or involve other health professionals will depend on:

- the needs and preferences of the person with diabetes

- your qualifications, knowledge, skills and confidence to address elevated anxiety symptoms

- the severity of the anxiety symptoms, and the context of the problem(s) whether other psychological problems are also present, such as diabetes distress or depression

- your scope of practice, and whether you have the time and resources to offer an appropriate level of support

If you believe referral to another health professional is needed:

- explain your reasons (e.g. what the other health professional can offer that you cannot)

- ask the person how they feel about your suggestion

- discuss what they want to gain from the referral, as this will influence to whom the referral would be made

ASSIST

Neither elevated anxiety symptoms or anxiety disorders are likely to improve spontaneously29, so intervention is important. The stepped care approach provides guidance on how to address elevated anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders in clinical practice.30-32

Once an anxiety disorder has been confirmed by a clinical interview, and if you believe you can assist the person:

- Explain the appropriate treatment options (see Box 7.1), discussing the pros and cons for each option, and taking into account the context and severity of the anxiety disorder, the most recent evidence about effective treatments (e.g. a collaborative and/or a stepped care approach) and the person’s knowledge about, motivation, and preferences for, each option.

- Offer them opportunities to ask questions.

- Agree on an action plan together and set achievable goals for managing their anxiety disorder and their diabetes. This may include adapting the diabetes management plan if the anxiety disorder has impeded their self-care.

- Provide support and treatment approaches appropriate to your qualifications, knowledge, skills and confidence. For example, you may be able to prescribe medication but not undertake psychological intervention or vice versa.

- Make sure the person is comfortable with this approach.

- At the end of the conversation, consider giving them some information to read at home. At the bottom of this page there are several resources that may be helpful for a person with diabetes who is experiencing an anxiety disorder. Select one or two of these that are most relevant for the person; it is best not to overwhelm them with too much information.

Some people will not want to proceed with treatment, at first. For these people, provide ongoing support and counselling about anxiety disorders to keep it on their agenda. This will reinforce the message that support is available and will allow them to make an informed decision to start treatment in their own time.

Box 7.1: Treating anxiety disorders

It is not within the remit of this guide to recommend specific pharmacological or psychological treatments for anxiety disorders in people with diabetes. Here are some general considerations based upon the evidence available at the time this guide was published:

First-line pharmacological treatment for generalised anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder and panic disorder is usually selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) Pharmacological treatment is not standard first-line treatment for specific phobias.

First-line psychological intervention for generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorder and specific phobia is usually cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Where avoidance behaviour is present, CBT should be combined with exposure.

The current evidence base does not support combining pharmacological and psychological approaches for generalised anxiety disorder or social anxiety disorder. Combined psychological intervention and pharmacological treatments can be beneficial for panic disorder.

Some medications used to treat mental health problems (e.g. antidepressants, anxiolytics, neuroleptics) can have adverse side effects, such as weight gain and metabolic abnormalities, and are associated with insulin resistance. Benzodiazepines are generally not recommended as a first-line treatment due to the risk of addiction. Before prescribing such medications, consider the risks and benefits and their appropriateness for the individual.

There is evidence for applying stepped care and collaborative care models for anxiety disorders in the general population. A recent trial found a stepped care approach to be effective for reducing anxiety symptoms in people with diabetes.

Early intervention is likely to benefit people with subthreshold anxiety disorder. Little research has been conducted into the effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological interventions. A stepwise approach has been proposed, beginning with watchful waiting and gradually increasing the intensity of intervention as symptoms persist or increase.

ASSIGN

The vast majority of specialist diabetes services in the UK do not have an integrated mental health professional, such as a clinical psychologist, to refer to. Therefore, the majority of referrals will be made to professionals outside the diabetes service. These might include:

- A general practitioner to undertake a clinical interview and diagnose major depression, and/or make a referral to an appropriate mental health professional, and prescribe and monitor medications. An extended appointment is recommended.

- A psychologist to undertake a clinical interview and provide psychological therapy (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy or interpersonal therapy).

- A psychiatrist to undertake a clinical interview, , and prescribe and monitor medications. A GP referral is usually required to access a psychiatrist. Referral to a psychiatrist is likely to be necessary for complex presentations (e.g. if you suspect severe psychiatric conditions, such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, or complex co-morbid medical conditions).

- Community Mental Health Teams can help the person find ways to effectively manage situations that are contributing to their anxiety or inhibiting their treatment (e.g. trauma or life stresses), using psychologically-

- Improving Access to Psychological Therapies – Long Term Conditions (IAPT-LTC) are accessible in some areas in England. These services focus on people with long term conditions, including diabetes. Local contact details can be found online (see ‘Resouces’ section).

If possible, consider referring the person to health professionals who have knowledge about, or experience in, diabetes. For example, if their diabetes management is affected by their anxiety disorder, they may need a new diabetes management plan that is better suited to their needs and circumstances at the time.

This might require collaboration with a GP or diabetes specialist (e.g. an endocrinologist, diabetes specialist nurse, and/or diabetes specialist dietitian).

If you refer the person to another health professional, it is important:

-

that you continue to see them after they have been referred so they are assured that you remain interested in their ongoing care

-

to maintain ongoing communication with the health professional to ensure a coordinated approach.

ARRANGE

Depending on the action plan and the need for additional support, it may be that more frequent follow-up visits or extended consultations are required until the person feels stronger emotionally. Encourage them to book a follow-up appointment with you within an agreed timeframe to monitor progress and address any issues arising. Telephone/ video conferencing may be a practical and useful way to provide support in addition to face-to-face appointments.

Mental health is important in its own right but it is also likely to impact on the person’s diabetes self-management and their physical health. Therefore, it is important to follow up to check that they have engaged with the agreed treatment.

At the follow-up appointment, revisit the plan and discuss any progress that has been made. For example, you might say something like, ‘When I saw you last, you were feeling anxious. We made a plan together to help you with that and agreed that I would refer you to see a psychologist. Have you had an appointment with the psychologist]? How has this worked out for you?’

Case Study

- Deepa

- 37-year-old woman living with her partner, George

- Type 1 diabetes, (diagnosed 21 years ago)

- Health professional: Dr Ariadne Pappas (Diabetologist)

Be AWARE

Deepa has not been feeling herself lately. She finds herself worrying a lot about her diabetes and other aspects of her daily life. Often she feels irritable and tired for no reason, and wonders if this is related to her diabetes (e.g. lack of sleep due to late night hypoglycaemia). She likes things in her life to be in order, so this change from the ordinary concerns her. Deepa tells Dr Pappas that she doesn’t know what to do; she hopes that Dr Pappas will have some answers for her. Dr Pappas listens to Deepa’s concerns and acknowledges that some of the symptoms may be related to Deepa’s diabetes. However, Dr Pappas does not want to rule out other causes yet because she is aware that irritability and tiredness are common symptoms of a range of conditions.

ASK

Through open-ended questions, Dr Pappas learns more about Deepa ’s symptoms: sometimes Deepa sweats or shakes, and when this happens her heart beats faster than usual. This has happened to Deepa a few times on the train to work in the city. It is physically and mentally draining for Deepa; it makes her feel ‘on edge’. Sometimes a quick blood glucose check shows she is having a ‘hypo’, which would explain her symptoms, but most of the time her glucose levels are in target. Her moods are affecting her relationship with her partner, George, and this causes her even more stress and worry.

ASSESS

Dr Pappas decides further assessment is needed. She invites Deepa to complete two screening questionnaires: for anxiety (GAD-7) and depression (PHQ-9). Deepa scores 13 on the GAD- 7, suggesting that she is experiencing moderate levels of anxiety symptoms. She also scores 6 on the PHQ-9, indicating mild depressive symptoms. Dr Pappas checks the file for her most recent HbA1c and asks to look at Deepa’s recent blood glucose readings. These and other assessments reveal no physiological causes for the anxiety symptoms.

ADVISE

Dr Pappas explains the questionnaire scores to Deepa and asks her if this fits with how she has been feeling lately. She also explains to Deepa the symptoms of anxiety and depression, and reassures her that there are several treatment options. These include medication, psychological therapy, or a combination of these. Deepa appears interested in seeking treatment and support. Dr Pappas advises Deepa to make an appointment for an extended consultation with her GP as soon as possible to discuss the best treatment options for her. She explains that a GP can diagnose the anxiety and, if necessary, organise psychological treatment and prescribe medication. She offers Deepa plenty of opportunity to ask questions, and Deepa agrees to see her GP. Dr Pappas gives Deepa a copy of the ‘Diabetes and Anxiety’ Fact Sheet.

ASSIGN

With Deepa's permission, Dr Pappas writes a letter to Deepa’s GP and includes the scores and interpretation of the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 questionnaires.

ARRANGE

Dr Pappas and Deepa agree that Dr Pappas will write a letter to Deepa’s GP, with the agreed plan that Deepa will make an appointment for an extended consultation with her GP for the following week. Dr Pappas and Deepa arrange a follow-up appointment once she has seen her GP. With agreement from Deepa Dr Pappas telephones Deepa’s GP to check that they will make an appointment available to her in a timely manner. Dr Pappas encourages Deepa to contact her via telephone if she has any difficulty getting an appointment with the GP.

Case Study

- Ned

- 47- year-old man living with his wife Faye and their children

- Type 2 diabetes, (diagnosed 3 months ago) managed without medication; dyslexia

- Health professional: Mai Nguyen (and dietitian)

Be AWARE

Ned was recently diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes, and his dyslexia is causing him some challenges with self-management. His GP has referred him to Mai for diabetes education. Mai and Ned have met twice and have begun to build a good rapport. Mai senses that Ned has adjusted quite well to the diagnosis of diabetes, but feels that he needs to build his confidence in managing the condition. They have been working on this together. Mai has observed Ned to be quite an anxious person, as he:

- fidgets during consultations

- gets visibly nervous (shaky hands, sweaty palms), particularly when practising reading food labels; his nervousness seems to be related to reading and interpreting written information

- expresses worries about whether he is getting his diabetes management ‘right’.

Mai has started to develop concerns about Ned’s level of anxiety symptoms, so when he mentions that he has not been sleeping well she decides to investigate further.

ASK

Mai enquires about why Ned has not been sleeping. He tells her that ‘I can’t switch my brain off... I worry ‘bout my dad – he’s not been well, and how the kids are going at school, and now there’s this diabetes thing... and the little things worry me too – noises at night, whether I locked the car... Faye says I’m a “worry wart”. She won’t say it, but it annoys her... I can’t help it’. Mai asks Ned whether his level of worry bothers him too, and he tells her that it does. He says he worries ‘during the day sometimes, but the nights are worse’.

ASSESS

Mai tells Ned that it is quite common for people with diabetes to develop problems with anxiety and worry. She asks Ned whether he will answer some questions to help better understand his worries. Ned agrees, so Mai:

- opens a copy of the GAD-7 on her computer screen

- reads the GAD -7 questions and response options aloud to Ned and asks him to respond to each question.

Ned scores 17, indicating severe anxiety symptoms.

ADVISE

Mai explains that Ned’s score is high – that this is more than just worry – it indicates a possible diagnosis of anxiety. She explains what this is and asks him if this fits with how he has been feeling lately.

To reassure him, she says, ‘Now that we know that there is a problem, there are things we can do to help you. The first step is for you to see your GP. If you do have an anxiety disorder, then he will confirm it and he can help you to treat it, too, with medication or a referral for psychological support, or both. Treatment will help to lower your worry and anxiety symptoms, which will help you to sleep better’.

Ned expresses concern about what people might think, especially at work on the building site. Mai tells him that anxiety is very common, with one in five men experiencing an anxiety disorder at some stage in their life.8 Mai reassures Ned that it is his choice who he tells (or doesn’t tell) about his anxiety. She suggests he talks initially just with the people he trusts, such as his wife and GP.

ASSIGN

Mai explains that Ned can continue to see her for diabetes education but he will also need to see his GP to address the anxiety, as this is outside her expertise. She proposes that she write a referral to his GP, including his questionnaire responses and scores. Ned agrees to make an appointment with the GP. Mai suggests that he sees the GP as soon as possible, and that he requests an extended consultation so that they have plenty of time.

ARRANGE

They agree that Ned will return to see Mai in one week. They would like to continue with the diabetes education, and Mai would like to check Ned’s progress with his GP regarding his anxiety symptoms. Due to the severity of Ned’s symptoms, Mai calls his GP to check that the referral was received and that an appointment will be made available to him as soon as possible.

Questionnaire: Generalized Anxiety Disorder Seven (GAD-7)

Find the GAD-7 questionnaire, and information on how to use it on the full Diabetes and emotional health PDF (3MB)

Resources

For health professionals

Peer-reviewed literature

- Association of diabetes with anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Explores the relationship between diabetes and anxiety; in particular whether diabetes is associated with increased risk of anxiety disorders and symptoms.

Source: Smith KJ, Beland M, et al. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2013;74:89-99.

- Anxiety disorders: assessmentand management in general practice

Describes the diagnosis, assessment and management of anxiety disorders in general practice.

Source: Kyrios M, Moulding R, et al. Australian Family Physician. 2011;40(6):370-374.

Finding Specialist Services

- Find a psychologist:

https://www.bps.org.uk/public/find-psychologist. This directory of Chartered Psychologists is provided by the British Psychological Society. Chartered psychologist are listed by locality and specialist area of interest. - Improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) : Find a service: https://www.nhs.uk/Service-Search/Psychological-therapies-(IAPT)/LocationSearch/10008

Guidelines

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guidelines (NICE): Anxiety

Clinical guidelines for the care and treatment of anxiety

Source: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines (NICE) (2014). Anxiety Disorders. Accessed online September 2018: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs53

Books

- Management of mental disorders (5th edition)

A book that provides practical guidance for clinicians in recognising and treating mental health problems, including generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia and panic disorder. The book also includes worksheets and information pamphlets for people experiencing these problems and their families.

Source: Andrews G, Dean K et al. CreateSpace. 2014.

Additional information: Sections of this book (e.g. treatment manuals and worksheets) are freely available to download from the ‘Support for clinicians’ section of the Clinical Research Unit for Anxiety and Depression (CRUfAD) website at www.crufad.org

For people with diabetes

Select one or two resources that are most relevant and appropriate for the person. Providing the full list is more likely to overwhelm than to help.

Information

- Mind:

Mental health charity offering information (and telephone and online support), including discussion forums.

Contact: Tel: 03001233393 Email:info@mind.org.uk

Website: www.mind.org.uk

- Mind’s specific anxiety information

Information about anxiety, including possible causes and how to access treatment and support.

-

Anxiety and Diabetes Fact Sheet:

Description: A factsheet specifically to accompany this guide, giving information about anxiety and how to manage it. You can download it here (PDF, 47KB)

- Rethink Mental Illness, Guide to Anxiety:

Description: A factsheet from the charity Rethink Mental Illness, with sections including types of anxiety, causes and ways to get treatments

URL: https://www.rethink.org/resources/a/anxiety-disorders-factsheet

- Anxiety. An NHS Self-Help Guide:

Description: A 20-page booklet from the Northumberland Tyne and Wear NHS Trust containing information and practical

ways to manage anxiety

website: https://web.ntw.nhs.uk/selfhelp/

Books

- Mind Over Mood: Change How You Feel by Changing the Way You Think (1995, Greenberger, D. and Padesky, C. Guilford).

A self-help book to learn how to change unhelpful thoughts and solve problems, with a chapter specially focusing on anxiety.

website: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Mind-Over-Mood-Second- Changing/dp/1462520421/ref=pd_lpo_sbs_14_img_0/261-8472430- 1202157?_encoding=UTF8&psc=1&refRID=92NW5NSGVYNGP145B6HX

- Overcoming Anxiety: A Self-Help Guide Using Cognitive Behavioral Techniques (2009, Kennerley, H.,Robinson Books).

A self-help book to learn how to overcome a range of anxieties, in a step-by-step format.

- Diabetes and Wellbeing: Managing psychological and Emotional Challenges in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes (2013, Nash, J., John Wiley and Sons).

A book written by Dr Jen Nash, Clinical Psychologist who lives with Type 1 diabetes, with a chapter on managing the anxiety of living with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes

Support

- Diabetes UK Online Support Forum

An online discussion forum for people living with diabetes to access information and support, with many different topics being discussed. The Welcome page explains more about it and where to find support for specific aspects of your diabetes, including anxiety

Website: https://forum.diabetes.org.uk/boards/forums/welcome-and-getting-started.37/

- Diabetes UK information on emotional wellbeing and support

A website page giving information and ideas of ways to access emotional support

Website: www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/life-with-diabetes/emotional-issues

- Type 1 Resources:

A collection of useful websites and resources to help manage life with type 1 diabetes:

Website: www.t1resources.uk/resources/managing-life/

- Find a psychologist:

This directory of Chartered Psychologists is provided by the British Psychological Society. Chartered psychologist are listed by locality and specialist area of interest.

website: www.bps.org.uk/public/find-psychologist.

- Improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) :

IAPT is an NHS service providing treatment for anxiety and depression. There is a search function to find local IAPT services on the NHS website:

Website https://www.nhs.uk/Service-Search/Psychological-therapies-(IAPT)/LocationSearch/10008

"People have no idea how hard it is living with diabetes. It’s exhausting, it’s constant, and they just seem to think that “Oh well, you take this much insulin and you eat this much food and you’ll be fine” but it’s just not like that at all... the issues, the difficulties, the day-to-day dramas, and the toll it takes emotionally and psychologically is not understood, and I think it needs to be." - Person with type 1 diabetes

See Diabetes and emotional health PDF (3MB) for our full list of references

Disclaimer: Please note you may find this information of use but please note that these pages are not updated or maintained regularly and some of this information may be out of date.