Key messages

- Psychological barriers to insulin use are the negative thoughts or feelings that people with diabetes may have about starting, using, or intensifying insulin.

- Of those people with type 2 diabetes for whom insulin is clinically indicated, around one in four report being ‘not at all willing’ to start insulin.

- People already using insulin are sometimes reluctant to optimise or intensify insulin

- (but no prevalence data are available). One in 10 people with type 2 diabetes using insulin are dissatisfied with it.

- Psychological barriers can be associated with the delay, reduction or discontinuation of insulin use, which can lead to sub-optimal blood glucose levels and increased risk of diabetes complications.

- A brief questionnaire, such as the Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale (ITAS), is useful for identifying psychological barriers to insulin use.

- There is little empirical evidence about the best ways to minimise psychological barriers to insulin. Recommendations based on clinical experience emphasise anticipating and acknowledging psychological barriers, and then working together with the individual to develop strategies to overcome them.

Practice points

- Help people to understand the natural course and progressive nature of type 2 diabetes, and the likelihood that their treatment will change over time. Emphasise that needing insulin does not indicate that they have ‘failed’.

- Be aware that people using insulin, as well as those not yet using insulin, experience psychological barriers to insulin. Every person will have different concerns; ask them what their concerns are, rather than making assumptions.

- Monitor for signs of psychological barriers to insulin, particularly when a person’s HbA1c has been above target for some time, and there is no sign that they are ready to transition to or intensify insulin.

How common are psychological barriers to insulin use?

|

|

What are psychological barriers to insulin use?

People with type 2 diabetes often have negative thoughts or feelings about starting, using, or intensifying insulin. This is also known as ‘psychological insulin resistance’ or ‘negative appraisals of insulin’. Concerns about insulin among people with type 2 diabetes can be grouped into five main themes:

- concerns about medications (e.g. doubts about effectiveness; dependence on insulin) and possible side effects (e.g. weight gain, hypoglycaemia)

- anxieties about injections (e.g. fear of injections, needles or pain; experiences of pain, bruising, scarring or sensitivity from injections)

- lack of confidence/skills (e.g. in their ability to use insulin, coping with a complex regimen, injecting in public)

- impact on self-perception and life (e.g. feelings of personal failure or self-blame for needing insulin, injections interfering with daily activities; social stigma)

- fears about diabetes progression (e.g. insulin as a sign that diabetes is ‘getting worse’, insulin as the ‘last resort’, mistaken beliefs that insulin leads to diabetes complications).

A person with diabetes may be aware of the benefits of insulin but still have worries or concerns about using insulin.

Concerns about insulin use can delay the transition from oral medication to insulin, or among those already using insulin, this could result in misuse or stopping insulin. This has consequences for medical and psychological outcomes, including:

- glucose levels (including HbA1c) above recommended targets for prolonged periods, leading to increased risk of developing long-term complications

- reduced satisfaction with treatment

- impaired quality of life

- increased burden/costs to the individual and the healthcare system.

For some people, an alternative option to insulin may be a non-insulin injectable (see Box 5.1).

Box 5.1: What about other injectable therapies?

Typically, people with type 2 diabetes prefer tablets to insulin. In recent years, new (non-insulin) injectable agents have become available. Like insulin, incretin-based agents (e.g. GLP-1) reduce blood glucose and require injections but have the advantage of a lower risk of hypoglycaemia and weight gain.

In clinical trials, people with type 2 diabetes report greater treatment satisfaction and quality of life using GLP-1s compared to insulin. It is possible that the perceived benefits of GLP-1s outweigh the perceived shortcomings of injections.16 Further research is required to evaluate this in clinical practice. Note that GLP-1 agents may be contraindicated for some people.

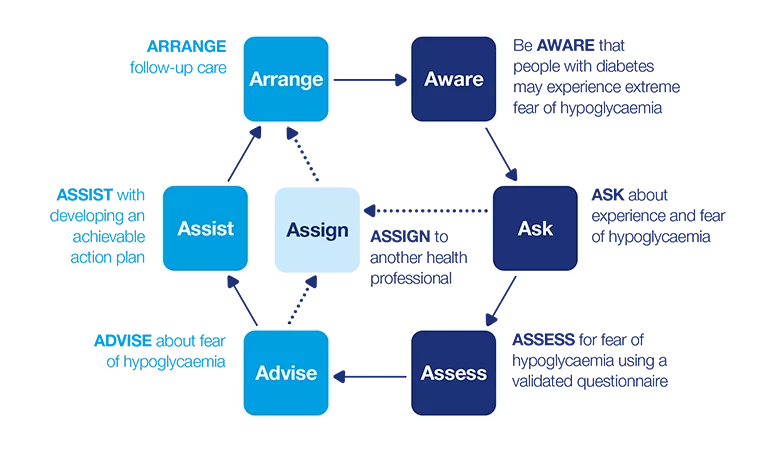

7 As model: Psychological barriers to insulin use

This dynamic model describes a seven-step process that can be applied in clinical practice. The model consists of two phases:

- How can I identify psychological barriers to insulin use?

- How can I support a person with psychological barriers to insulin use?

Apply the model flexibly as part of a person-centred approach to care.

How can I identify psychological barriers to insulin use?

Be AWARE

Individuals with psychological barriers to insulin may show this by:

- avoiding or being reluctant to talk about, begin, or intensify insulin use

- expressing concerns or becoming upset at the suggestion of beginning or intensifying insulin

- expressing concerns about injecting or possible side effects of insulin (e.g. complexity of injection technique, effect on lifestyle, perceptions of self and others, weight gain)

- ‘negotiating’ to ‘do better’ with their current management plan to improve diabetes outcomes

- ‘dropping out’ (e.g. missing appointments, filling fewer insulin prescriptions)

- appearing not to care about, or seeming uninterested in, managing their diabetes

- talking about discontinuing insulin use (now or in the future)

- misusing insulin (e.g. missing doses or taking smaller doses than recommended) or stopping insulin altogether.

Some people may be embarrassed to raise concerns about insulin (see Box 5.2).

Box 5.2: Remarks indicating possible psychological barriers to insulin use

- 'i worry i'll never be able to get off insulin'

- 'Insulin means you run the risk of hypos'

- 'No more spontaneity'

- 'It's not fair; i've tried so hard with diet, exercise and medication'

- 'Needing insulin means i haven't done well managing my diabetes - I have failed, this is the end of the road.

- 'Others will worry a lot about me'

- 'I don't like needles'

- 'Insulin means my diabetes is worse'

- 'Insulin is too complicated and overwhelming - i will never be able to learn how to inject and get the right dose'

- 'i can improve my blood glucose/HbA1c numbers without insulin - just give me some more time to improve my numbers/lose weight/exercise more etc'

- 'Insulin won't help my diabetes - nothing good will come of insulin'

- 'Since starting insulin my diabetes has not improved but I have gained all this weight'

ASK

Ask open-ended questions during the consultation to explore the individual’s beliefs and concerns about insulin. Have this conversation:

- shortly after the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes

- when you notice signs of concerns or worries about insulin

- if the person has sub-optimal HbA1c despite being on (near) maximal oral agents

Before asking the following questions for the first time, make sure the person realises that diabetes is a progressive condition and that they are likely to need insulin in the future. Raise the use of insulin as a potential treatment option early (soon after diagnosis). Continue to have the conversation when you notice signs of psychological barriers to insulin, or when the person expresses concerns about insulin.

For example, for people who are not yet using insulin, you could ask:

- ‘How do you feel about going on insulin [now or in the future]? Can you tell me more about that?’

- ‘What questions do you have about insulin?’

- ‘How do you think insulin might affect your health and lifestyle?’

- ‘What do you think might be the benefits of using insulin for you?’

- ‘What do you think might be the disadvantages of using insulin for you?’

- ‘Some people have concerns about insulin. What concerns do you have? What is your main concern?’

- ‘What have you heard from other people with diabetes who use insulin?’

Or, for people who currently use insulin, you could ask:

- ‘Tell me about your experiences using insulin. How is that going?’

- ‘How do you feel about using insulin?’

- ‘What concerns do you have about insulin? Which is your main concern?’

- ‘What questions do you have about insulin?’

- ‘How does insulin make your [life/diabetes] easier?

- ‘How does insulin make your [life/diabetes] more difficult?’

- ‘What advantages have you noticed when using insulin?’

- ‘What disadvantages have you noticed when using insulin?’

It is important to establish whether the person’s concerns are only related to insulin, or related to their diabetes more broadly. To explore their broader concerns about diabetes, you might like to ask a question such as, ‘What is the most difficult part of having diabetes for you? Can you tell me more about that?’

If the person indicates that they have concerns about using insulin, you may want to explore this further. Using a validated questionnaire will help you both to identify additional barriers that were not raised through conversation. Importantly, it will also give you a benchmark for tracking an individual’s barriers to insulin use over time.

However, only use a questionnaire if there is time during the consultation to talk about the scores and discuss with the person what is needed to address the identified concerns about insulin.

ASSESS

Validated questionnaire

The Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale (ITAS; 20 items) is the most widely used measure of psychological barriers to insulin use. A copy is included on the Full PDF version of this guide (3MB) of this guide

Each item is scored on a five-point rating scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items form two subscales:

- positive appraisal of insulin (items 3, 8, 17 and 19): higher scores indicate more positive attitudes to insulin

- negative appraisal of insulin (all remaining items): higher scores indicate more negative attitudes to insulin.

There is no recommended cut-off value to indicate the presence or absence of psychological barriers to insulin use.

Subscale total scores may be valuable for assessing change over time. Responses to individual items will be helpful in guiding the conversation about insulin use, and for understanding and addressing concerns.

Invite the person to explore their concerns (negative attitudes) about insulin in a conversation about their responses, for example, ‘I note here that you are concerned about [issue]. Can you tell me more about that?’ If the person has several concerns, ask which are their priority issues, for example, ‘You seem to have a few worries about insulin. Which of these would you find most helpful to talk about today?’

Additional considerations

Be aware of and explore other factors that may contribute to a person’s concerns about using insulin, such as:

- the complexity of their current medication regimen in addition to insulin (e.g. other medications, the number of daily doses)

- cultural factors (e.g. health beliefs, language barriers, their level of trust in the healthcare system and treatments)

- health literacy

- any physical and mental impairment or disability (e.g. vision or hearing loss, dexterity, memory, cognitive function)

- costs and access (e.g. insulin and related supplies, medical appointments)

- practical skills (e.g. planning, problem solving)

- the beliefs and attitudes of their partner, family members and wider social network.

How can I support a person with psychological barriers to insulin use?

The decision to begin, intensify and continue insulin use is the choice of the person with diabetes. Your role is to help them make an informed choice by providing open communication, information and support. It is your duty-of-care to make sure they are informed about the consequences of their decision. Keep in mind that even if they are not open to the idea initially, they may become more open over time (e.g. through discussion, education).

ADVISE

Talk with the person about insulin and its role in diabetes management (relating it back to their ITAS responses, when assessed):

- acknowledge the specific barriers the person has raised

- acknowledge that it is common to have questions and concerns

- reassure them that needing insulin does not indicate they have ‘failed’

- advise that many people need insulin as a part of the natural progression of diabetes

- tell them that people who use insulin find it beneficial because it is a powerful way to keep blood glucose within an optimal range to prevent long-term complications, it allows for more flexibility with food and planning of meals and it improves their energy levels

- advise that insulin use may begin with just one or two injections per day

- make it clear that it is the individual’s decision whether or not to use insulin and you would like to assist them in making an informed choice

- offer the person opportunities to ask questions

- make a joint plan about the ‘next steps’ (e.g. what needs to be achieved and who will help).

Choose your words carefully. If the person views insulin as a veiled threat or associates insulin with a sense of ‘failure’, they may want to continue negotiating to delay insulin. They may feel that if they can just ‘do a bit better’ with their current management plan they will not need insulin – and this is unlikely to be the case.

Next steps: ASSIST or ASSIGN?

As psychological barriers to insulin use are intertwined with diabetes management, they are best addressed by a diabetes health professional or GP (if they are the main health professional). If you have the skills and confidence, support the person yourself, as they have confided in you for a reason. A collaborative relationship with a trusted health professional and continuity of care are important in this process.

In most cases, you will be able to address psychological barriers to insulin use without referral, through education and counselling. The following factors will inform your decision:

- your scope of practice, and whether you have the time and resources to offer an appropriate level of support

- your knowledge, skills and confidence to address the identified barriers

- the needs and preferences of the person with diabetes

- the severity of the psychological barriers (e.g. worries about injections versus injection phobia)

- whether other psychological problems are also present, such as depression or an anxiety disorder.

If you believe referral to another health professional is needed:

- explain your reasons (e.g. what the other health professional can offer that you cannot)

- ask the person how they feel about your suggestion

- discuss what they would like to gain from the referral, as this will influence to whom the referral will be made.

ASSIST

Recent studies have investigated strategies to overcome psychological insulin resistance. Demonstrating the injection process, explaining the benefits of insulin, and a collaborative style were the three most helpful actions of health professionals in facilitating insulin initiation. These recommended strategies are based on recent research, clinical experience, and expertise. For most people, an initial reluctance to use insulin can usually be overcome.

Common barriers and practical strategies for minimising these barriers are listed in Appendix D. Not all strategies will suit everyone, so you will need to work with the person to tailor appropriate solutions to their specific barriers, needs and preferences. Discussing the individual’s responses to the ITAS items is useful for this purpose.

For people who are new to insulin use, it will often be most appropriate to begin by exploring their thoughts and feelings about insulin. Postponing other changes to their treatment regimen will help to prevent additional disruptions to their routine.

Three key strategies that may be particularly useful are: demonstrating the insulin injection process; ‘decisional balancing’, and offering a time-bound ‘insulin trial.

Demonstrate the insulin injection process

People who were initially unwilling but then initiated insulin, have said that the most helpful action of their health professional was to demonstrate the injection process. People who had experienced a demonstration of the process were less likely to delay insulin initiation. This can be done in three easy steps. First, show the person an insulin pen, and the size of the needle – many people are surprised by how small the needle is. The next step is to demonstrate the process of giving an injection, to show how simple it is. Finally, invite the person to try an injection for themselves, during the consultation with you. Invariably, this process helps a person to realise that injecting insulin is not as difficult or as painful as they imagined it would be.

Decisional balancing

‘Decisional balancing’ is a technique used in motivational interviewing. It enables the person to explore the relative merits of each treatment option (and how they feel about this). This tool helps to build rapport and helps you assess their readiness for change. It is a way of supporting the person to work through the ambivalence in their thoughts and to make an informed decision.

Invite the person to list the three most relevant pros and cons per treatment (preferably in writing). If the person lists only one, encourage them to list one or two more (e.g. ‘What other pros/cons might there be?’).

After they complete the tool, you can use their responses as the basis for a conversation. Rather than starting with problems or concerns about insulin, begin with the positives of their current treatment, and then discuss the perceived disadvantages. This may help the person realise for themselves that remaining on the current treatment is not ideal. The next step is to explore the extent to which switching to insulin would be a way to overcome these disadvantages. This elicits the advantages of using insulin. Finally, ask which of the disadvantages of using insulin would be easiest for the person to overcome and brainstorm strategies.

Note that the ‘pros’ and ‘cons’ of each treatment may not be of equal importance to the individual.

The ‘Diabetes Medication Choice’ decision aid31 may be a helpful tool for comparing treatment options in terms of various concerns (e.g. side effects, regimen).

An ‘insulin trial’

An ‘insulin trial’ is a way to encourage the person to ‘experiment’ with insulin for a period of time that you both agree on. The length of the experiment should depend on the intended outcomes. For example, a one-month ‘trial’ may be long enough for a person to experience how they can fit an insulin regimen into their lifestyle. Extending the ‘trial’ to three months will enable them to notice improvements in glycaemic outcomes (HbA1c).

You can view the decisional balancing tool on the full PDF.

Make sure the person feels confident that they have the option of reverting back to their previous treatment if this experiment has not worked out for them. At the end of the experiment, review their experience together: reflect on the perceived advantages and disadvantages and whether or not these were expected.

ASSIGN

If a decision is made to refer, consider:

- a diabetes specialist nurse or other diabetes health professional (e.g. an diabetologist or a dietitian) for self-management training (e.g. injection technique, carbohydrate counting) and support

- a mental health professional (preferably with an understanding of diabetes and insulin) if the problem is ongoing, or if it is evident that there is an underlying personal or psychological problem (e.g. needle phobia, an anxiety disorder), or the person with diabetes feels that it could benefit them

- a structured diabetes education group, because insulin initiation in a group setting is as effective as an individual session and takes half the time; it also offers important opportunities for people to share their concerns and ideas about insulin.

If you refer the person to another health professional, it is important:

- that you continue to see them after they have been referred so they are assured that you remain interested in their ongoing care

- to maintain ongoing communication with the health professional to ensure a coordinated approach.

ARRANGE

Make any necessary arrangements for the person to receive the care you have agreed on:

- arrange a follow-up appointment; if the person is happy to do so, book a follow-up appointment while they are at your clinic

- use the follow-up appointment to oversee their progress, and to monitor and address any ongoing obstacles.

Be prepared to support the person more than usual during this time, for example, more frequent or extended consultations may be necessary. Telephone/video conferencing may be a practical and useful way to provide support in addition to face-to-face appointments.

"I know eventually I probably will have to go to insulin and that’s going to be an absolute pain... but then it’s going to be an absolute pain if I don’t do it. So that’s going to happen..." - Person with type 2 diabetes

Case study

- Bruce

- 72-year-old man, living with wife Martha

- Type 2 diabetes, managed with oral medications; overweight

- Health professional: Dr Amy Saunders (GP)

Be AWARE

Dr Saunders is concerned because, after some high blood glucose readings, Bruce has stopped bringing his blood glucose diary to his appointments. She has raised the idea of transitioning to insulin with Bruce, but he has insisted that ‘I’m sure I can get my blood sugar back down with some hard work and persistence’. Dr Saunders knows that it is common for people with diabetes to have concerns about starting insulin and suspects that Bruce may feel this way. She has, therefore, made a note in Bruce’s file to follow it up next time she sees him.

ASK

At the next appointment, she asks him how he is feeling generally and how he is feeling about his diabetes. Bruce says ‘I’m okay, but I have been finding things a bit tough because I just can’t keep my numbers down, even though I exercise daily and take my pills’. Dr Saunders reminds Bruce that they have spoken previously about insulin. Remembering that it can be helpful to anticipate and normalise diabetes-related concerns, she invites Bruce to share his feelings: ‘Some people do have concerns about insulin. How do you feel about it?’ Bruce tells Dr Saunders that his neighbour, Prue, has diabetes, and since she started insulin a year ago she has gained weight and developed vision problems. He says, ‘I’m not going to let that happen to me – I won’t start using insulin’.

ASSESS

Dr Saunders says, ‘It sounds like you do have some concerns about using insulin. Would you like to complete a questionnaire so we can better understand how you feel about it?’ Bruce agrees, so she gives him a copy of the ITAS.

Bruce’s responses show he has four main psychological barriers to insulin:

- ‘taking insulin means I have failed to manage my diabetes with diet and tablets’ (agree)

- ‘insulin causes weight gain’ (agree)

- ‘taking insulin means my health will deteriorate’ (strongly agree)

- ‘taking insulin helps to prevent complications of diabetes’ (strongly disagree).

ADVISE

Dr Saunders suspects that many of Bruce’s concerns can be resolved with discussion and education. She tells Bruce that she:

- would like to talk to him about his responses to the questionnaire

- would like to help him to better understand insulin treatment

- is not trying to pressure him into starting insulin

- just wants to make sure he is well informed about his treatment options.

Bruce agrees to have the conversation.

ASSIST

Dr Saunders begins by asking Bruce if he would like to say a bit more about his feeling of failure. She listens to his reply, then explains that many people need to use insulin for their diabetes, not because they have failed, but because it is the best way to manage their diabetes at that point. She explains that type 2 diabetes is a progressive condition and, after some time, many people need the treatment to be intensified to manage it effectively. Often, this means transitioning to insulin.

The doctor also talks with Bruce about the benefits of insulin, relating it back to his specific example of Prue. She explains, ‘Diabetes related complications, like Prue’s vision problems, are caused by the sugar in your blood remaining too high for too long. Insulin helps to lower the sugar in your blood and is the best method we have to do that effectively. I’ve suggested that you begin using insulin so we can prevent those kinds of health problems’. Dr Saunders also:

- Suggests that a short ‘trial’ of insulin (for about four weeks) might give him some experience and alleviate some of his concerns. She says, ‘Many of the people with diabetes I see have some concerns about insulin at first, just like you do. But I usually find that once they try it, it really helps them to feel better. If you don’t find it useful after a few weeks then we’ve learned that it’s not the right diabetes treatment for you at this time. I am wondering whether you will consider trying this, Bruce?’

- Explains the potential benefits of insulin in addition to better glucose levels – feeling less tired, fewer medications (he may be able to reduce the number of oral hypoglycaemic agents), and possibly having fewer side effects than the medications he is currently taking.

- Talks about the possibility of weight gain with insulin use and offers to write a referral to a local dietitian who could help him to prevent weight gain.

- Reassures him that he does not need to decide about the ‘insulin trial’ today.

- Recommends that he talk with his wife, Martha, and then come back to see her in a week.

- Suggests that he make an appointment with the receptionist before he leaves.

At the next appointment, Bruce tells Dr Saunders that he will give insulin ‘a try’. Dr Saunders draws up a diabetes care plan and writes a prescription for long-acting insulin, which he will need to inject once a day. She explains that Bruce will need to see the diabetes specialist nurse to learn about insulin (e.g. how it works, dosage, timing of injections, how long it will take to notice an effect, effects of food and exercise), injection technique, and hypoglycaemia (prevention, recognition, and treatment), and to have the dose adjusted. This will involve a couple of appointments and telephone calls. She gives him plenty of opportunities to ask questions.

ARRANGE

Dr Saunders writes a referral letter to the diabetes specialist nurse. with instructions about the starting dose and regular dose titration until Bruce’s next review. She suggests that Bruce comes back to see her in four weeks so they can discuss how he is going, but he can visit her sooner or speak to the diabetes specialist nurse if he has any problems or questions. At the next appointment, Bruce can decide whether he will continue to use insulin, and Dr Saunders will prescribe the most appropriate type and dose of insulin for him. Bruce agrees with this plan.

Case study

- Tina

- 44-year-old woman

- Type 2 diabetes, managed with twice-daily insulin injections

- Health professional: Angela Smith (diabetes specialist nurse), following a referral

Be AWARE

Angela has received a referral letter from Tina’s diabetologist, who explains Tina has had ‘sub-optimal HbA1c over the past year’ and has ‘recommended increasing her insulin dose from two to four daily injections, but she disagrees’. Angela is aware that many people experience psychological barriers to intensifying an insulin regimen and wants to explore Tina’s reluctance to increasing her insulin dose.

ASK

At their first appointment, Angela thanks Tina for coming and asks how she can help. Tina says, ‘I’m here because my doctor sent me’. Angela replies, ‘I understand that he has suggested some changes to your treatment plan, can you tell me more about that?’ Tina tells Angela about the plan to increase her insulin injections to four times daily. Angela asks Tina how she feels about that plan and Tina tells her she is ‘not happy’.

Angela asks about Tina’s experiences using insulin and how she feels about it. Tina responds that she is generally doing okay with her current insulin injections. Angela also explores whether there have been changes in Tina’s life in the past year that could explain her increasing blood glucose levels. Tina describes nothing that would contribute significantly to her elevated blood glucose levels or to her reluctance to increase the frequency of her insulin injections.

ASSESS

Angela asks Tina whether she would like to complete a brief questionnaire so they can both better understand her concerns about insulin. Tina agrees and completes the copy of the ITAS that Angela gives her.

Tina’s responses indicate four key psychological barriers to insulin:

- ‘managing insulin injections takes a lot of time and energy’ (agree)

- ‘injecting insulin is painful’ (agree)

- ‘taking insulin helps to maintain good control of blood glucose’ (disagree)

- ‘taking insulin helps to improve my energy level’ (disagree).

ADVISE

Before discussing Tina’s responses, Angela asks Tina what she thought of the questionnaire. Tina replies, ‘It was alright, quite good really – no-one has ever asked me these sorts of questions before’. She tells Angela that when she first began using insulin she had struggled with the injections. At the time, her diabetologist had demonstrated the insulin injection technique and he’d been ‘quite encouraging’. But months later, ‘I still hadn’t got the hang of it and I felt silly asking questions all the time. My numbers went up, and I felt less supported as time passed. I already struggle with two injections, how can he expect me to go to four? I just want to go back to tablets’. Angela responds that:

- it is common to feel distressed about diabetes from time to time

- Tina should not feel embarrassed about asking questions

- she has noticed a pattern in Tina’s ITAS responses – she feels pain while injecting and is not experiencing the expected benefits of insulin (for her blood glucose and energy levels).

ASSIST

Angela asks Tina to demonstrate her injecting technique using saline solution. Tina agrees and she injects the saline slowly and directly into her abdomen, then quickly withdraws the pen. Some of the saline dribbles down Riana’s abdomen as the pen is withdrawn. Angela asks whether Tina has noticed it leaking out before, and Tina replies, ‘Yes, but that’s normal isn’t it?’ Angela explains that it is not normal and she may not be getting all the insulin she needs, which might explain her high glucose readings. Angela also checks that Tina is rotating her injection sites regularly. Then Angela:

- demonstrates how to improve her injection technique so that it will be less painful and Tina will receive the full dose of insulin

- asks Tina to practise a few times until they both feel comfortable with Tina’s injection technique

- suggests that Tina continue with her current twice-daily injections for a few more weeks using the new technique, and Tina agrees with this plan.

ARRANGE

Before the consultation ends, Angela:

- checks whether Tina has any more questions or concerns

- encourages her to keep a record of her injections and blood glucose readings, so they can monitor her progress and devise a plan of action together if the numbers have not improved

- encourages Tina to also record her injection sites and level of pain while injecting, from 1 (no pain) to 5 (extreme pain), so they can check whether the new technique is helping to reduce her pain, and whether her pain is related to specific injection sites

- suggests that Tina visit Angela again in two weeks

- asks Tina when she will next see her diabetologist, which is three months from now. Angela confirms that this will allow enough time to see an improvement in Tina’s blood glucose levels as a result of the new technique.

Questionnaire: Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale (ITAS)

Find the ITAS questionnaire, and information on how to use it on the full Diabetes and emotional health PDF (3MB)

Resources

For health professionals

Peer-reviewed literature

- Psychological insulin resistance: a critical review of the literature. A systematic review of common causes of psychological insulin resistance and available strategies to reduce it. Source: Gherman A, Veresiu IA, et al. Practical Diabetes International. 2011;28(3):125-128d

- What’s so tough about taking insulin? Addressing the problem of psychological insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Practical tips for recognising and addressing psychological insulin resistance in clinical practice. Source: Polonsky WH, Jackson RA Clinical Diabetes. 2004;22(3):147-150.

Tools

- The diabetes mellitus medication choice decision aid: a randomized trial. A tool that can be used in consultations to facilitate decision-making regarding diabetes treatment. Source: Mullan JR, Montori VM, et al. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169(17):1560-1568. website: diabetesdecisionaid.mayoclinic.org

- Initiating insulin: How to help people with type 2 diabetes start and continue insulin successfully. Three tables presenting ‘The insulin conversation’; ‘Responses to patient’s questions about insulin’ and ‘Insulin education’. Source: Polonksy et al. International Journal of Clinical Practice 2017;71(8):e12973

- Peer support. A listing of opportunities for people with diabetes to share experiences and information with others living with diabetes. (See Appendix B)

- Motivational Interviewing in Diabetes Care. A book describing the consulting techniques of motivational interviewing, including a chapter on Insulin Use in Type 2 Diabetes Source: Steinberg and Miller, 2015. Guilford Press, New York website: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Motivational-Interviewing-Diabetes-Care-Facilitating/dp/1462521630

For people with diabetes

Select one or two resources that are most relevant and appropriate for the person. Providing the full list is more likely to overwhelm than to help.

Information

- Treating your diabetes with insulin. Diabetes UK’s web pages covering insulin treatment. Source Diabetes UK. website www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/managing-your-diabetes/treating-your-diabetes/insulin

- Concerns about starting insulin (for people with type 2 diabetes). Description: A fact sheet to accompany this guide, for people with type 2 diabetes who have concerns about commencing or intensifying insulin therapy. The leaflet can be downloaded from here (PDF, 42KB)

- Insulin myths and facts. A fact sheet that dispels some of the myths about insulin injections. It also lists questions for people with diabetes to consider and discuss with their health professional Source: American Diabetes Association. Clinical Diabetes. 2007;25(1):39

Support

Diabetes UK. Diabetes UK is the major organisation for support, information and research relating to diabetes. Its confidential Helpline is available to discuss concerns about starting insulin treatment. Phone: 0345 123 2399 Email: helpline@diabetes.org.uk. Website: www.diabetes.org.uk

Peer support - Factsheet. A fact sheet to accompany this guide, which gives people with diabetes information about peer support opportunities. The leaflet can be downloaded here (39KB)

See Diabetes and emotional health PDF (3MB) for our full list of references.

Disclaimer: Please note you may find this information of use but please note that these pages are not updated or maintained regularly and some of this information may be out of date.