A new study from the University of Birmingham reveals that lower levels of a protein that binds to vitamin D might be responsible for changes to the often overlooked alpha cells in the pancreas, and could help us learn more about the development of type 1 diabetes.

In type 1 diabetes, the pancreatic beta cells that produce insulin to prompt the cells of the body to absorb sugar from the blood are destroyed by the body’s own immune system. Until recently, we thought that the alpha cells which sit alongside beta cells in the pancreas and release glucagon – causing blood sugar to rise - were left alone during the immune attack. But over the last ten years, researchers have found that alpha cell function also seems to fail in some people with type 1 diabetes. Understanding more about how type 1 diabetes develops is key if we want to help people live better with their condition.

A new study published in Cell Reports, led by Diabetes UK funded researchers Dr Katrina Viloria, Prof Martin Hewison and Prof David Hodson at the University of Birmingham, sheds light on the role of alpha cells in type 1 diabetes. The team investigated a protein known as Vitamin-D-binding protein (DBP). It is already known that DBP is responsible for moving vitamin D around the body to different organs. This new study suggests it also plays a role in the function of the alpha and beta cells in the pancreas.

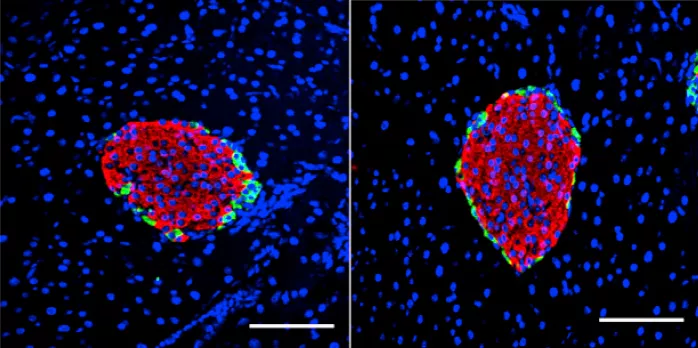

The researchers found that DBP was produced at very high levels in the alpha cells. To understand what role it was playing, they examined mice who had been genetically modified to not produce any DBP. They found that compared to normal mice, their alpha cells were smaller, less responsive to low glucose levels and produced less glucagon. They also noted that in mice with no DBP, their beta cells were more active when blood sugar was low. This is a surprising discovery, since beta cells normally only become active when blood sugar is high.

To learn if what they found in mice was similar in humans, the researchers looked at donated pancreases from people who had lived with diabetes. In those who had lived with type 1 diabetes over a longer period of time, or been diagnosed in later life, the alpha cells were smaller, and had lower levels of DBP, compared to people without diabetes. However, in people recently diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in early life, DBP levels appeared normal.

Dr Katrina Viloria said:

Alpha cells don’t tend to receive as much attention as beta cells in type 1 diabetes, yet their contribution to blood glucose should not be underestimated. Together with colleagues in Exeter, Oxford and Edmonton, we have been able to reveal DBP as a critical player in alpha cell function. We now want to understand whether DBP supplementation is able to modify glucagon release during type 1 diabetes.