Your donations allowed us to get 30 innovative new diabetes research projects off the ground in 2021. Our latest investment into diabetes research, totalling over £6.6 million, will help us make discoveries that could bring about life-changing advances in diabetes treatments and help us close in on a cure.

We’re funding new research into all types of diabetes and its complications. Here’s a snapshot of some of the exciting projects and remarkable researchers across the UK we’re supporting.

How do genes shape type 2 diabetes risk?

We awarded Dr Rachel Jennings at the University of Manchester our Harry Keen Fellowship – our largest research grant in 2021. The grant supports the most talented scientists working in the NHS to become diabetes research leaders of the future.

With funding of just under £1 million, Dr Jennings will find out how genes affect the risk of developing type 2 diabetes from the very start of life. She’s studying a particular gene and wants to find out if it disrupts how the pancreas and insulin-making beta cells develop in the womb. She then wants to understand how this gene influences someone’s risk of developing type 2 diabetes in much later life.

By better understanding the genetic roots of type 2 diabetes, Dr Jennings hopes we can unlock brand new approaches to preventing type 2 diabetes from ever developing. Learning more about a person's genetic risk of type 2 could lead to new, more personalised treatments to help people manage the condition.

Helping insulin-making cells to fight back

In type 1 diabetes, the immune system attacks and destroys insulin-making beta cells. But there’s a lot we don’t understand about what goes on in the pancreas when this happens.

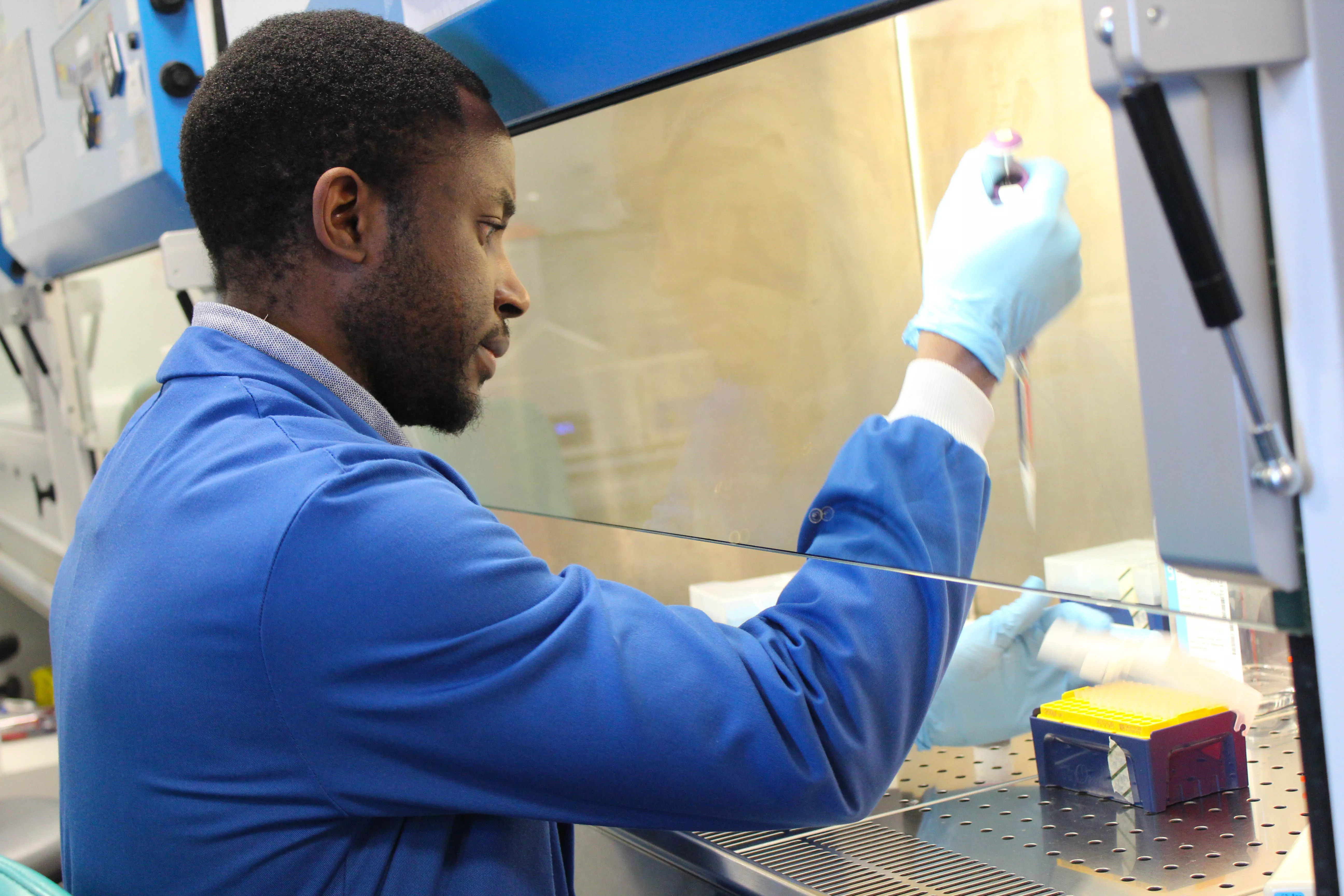

Professor Noel Morgan’s new project at the University of Exeter will find out if there's a way to allow beta cells to escape attack by the immune system. He’ll do this by growing beta cells in the lab and exposing them to different immune proteins, like they would be in the type 1 diabetes immune attack.

The team will use genetic engineering to change how the cells respond to the immune attack. This could show us ways that beta cells can resist attack and scientists can harness these insights to develop new treatments.

Our researchers are also working on new treatments to stop the immune attack, called immunotherapies. In the future, Professor Morgan hopes we can use these approaches alongside each other to both weaken the immune attack and strengthen beta cells’ defences against it.

Tackling the root cause of type 1 diabetes from two angles could give us the best possible chance of preventing type 1 completely in people who don’t yet have the condition. It could also help rescue surviving beta cells in people who’ve just been diagnosed.

Can anti-ageing drugs treat foot ulcers?

Too many people with diabetes still live with complications, but our research is finding more effective ways to prevent, manage and treat them. Foot ulcers are a common complication and can be difficult to heal. We’re funding Dr Holly Wilkinson at the University of Hull to explore a potential new treatment for slow-healing foot ulcers.

Scientists have discovered that cells in foot ulcers in people with diabetes go wrong. They become zombie-like, where they don’t die as they should, and turn surrounding cells into zombies too.

Our funding will support a PhD student in Dr Wilkinson’s lab to find out if these zombie cells play a role in slowing down healing in foot ulcers. They'll see if killing them with anti-ageing drugs could speed the healing up.

In the future, this could lead to a new treatment for people living with diabetes and foot ulcers. This could reduce the risk of more serious foot complications, like amputations, and help people to live better, healthier lives.

A healthier future after gestational diabetes

Dr Nerys Astbury at the University of Oxford will use our early-career research grant to look at the impact of gestational diabetes on women’s long-term health.

Gestational diabetes can increase the risk of complications during pregnancy and birth. But the condition goes away after the birth. Scientists don't know much about the longer-term impact of having had gestational diabetes.

Dr Astbury will compare health records of women who’ve had gestational diabetes with those who haven’t. She'll look for factors that affect the women's future health and wellbeing.

This information could be used to improve the care women who’ve had gestational diabetes receive after their pregnancy. This will help them avoid future health problems, like heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

Dr Astbury will also see if we can use information from health records to predict who is likely to develop gestational diabetes, so these women can be better supported to reduce their risk.

Dr Elizabeth Robertson, our Director of Research said:

"This week we’re celebrating 100 years since insulin was first used as a life-saving treatment for people with diabetes. This breakthrough and the century of diabetes research that followed has transformed how people live with the condition, but we recognise there is still a great deal to do. That’s why we continue to invest in exceptional diabetes research and researchers year on year.

“We hope that our 2021 crop of projects will help us to keep improving lives by finding better treatments, preventing diabetes complications and unearthing new insights that will help us move towards a cure. We can only make this investment in new research thanks to the generosity of our supporters – thank you for making our research possible.”