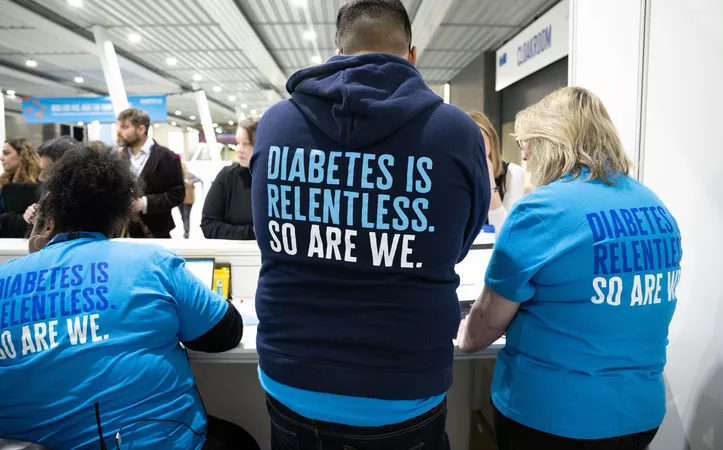

Our Professional Conference (DUKPC) brings together experts to share the latest breakthroughs in diabetes research and care. This year’s event wrapped in Glasgow last week and we’ve rounded up some of the stand-out studies and developments.

In this article:

- Finding type 1 diabetes early

- Dissecting diabetes stigma

- Exercise timing matters for managing type 2

- Every little (bout of exercise) helps in managing type 1

- Culprits in type 2 beta cell damage

- The rising challenge of early-onset type 2 diabetes

- Sleep could help explain the type 2-depression connection

Finding type 1 diabetes early

We heard the latest on research to identify and treat type 1 diabetes before it fully develops. Scientists can detect early signs of type 1 by looking for markers in the blood, called autoantibodies, long before symptoms appear.

The ELSA study, funded by us and Breakthrough T1D, is testing a screening programme in the UK to identify children who are very likely to develop type 1 in the future.

ELSA lead Professor Parth Narendran said over 25,000 children have already taken part. The families they've spoke to say screening is simple and valuable, though some have felt anxious while waiting for results.

Dr Rachel Besser from Oxford University spoke about the need for the right follow-on support and monitoring to make sure the benefits of screening are realised.

With our funding, she’s setting up a new registry which will track children and adults who’ve tested positive for autoantibodies. It will help us understand the best way to care for them, and help them to access to cutting-edge trials of immunotherapies, which hope to slow down the advancing immune attack.

In the US, the first-ever immunotherapy for type 1, teplizumab (Tzield), is already approved. Dr Kimber Simmons shared how it’s working there and got us excited for an UK decision, expected later this year.

The session made clear we’re standing at the edge of a monumental change in type 1 diabetes management, and the UK is getting ready.

Dissecting diabetes stigma

New insights highlighted the unique stigma challenges faced by people with diabetes from global majority communities.

A Diabetes UK survey of over 400 people from Black African, Black Caribbean and South Asian communities found they were more likely to come across stereotypes, myths and misconceptions about diabetes than the general population.

Healthcare interactions were a key issue. Nearly one in five reported stigma in healthcare settings, with nearly half experiencing it at least monthly. Many described judgmental, dismissive or culturally insensitive interactions with healthcare professionals.

And there were similar experiences with loved-ones. This can fuel mistrust and push people away from seeking care. We've found that nearly half of people with diabetes skip diabetes appointments because of stigma they’ve experienced.

Food was another source of stigma. Half of respondents reported being criticised or questioned about their eating habits – both by healthcare professionals and their own communities – compared to a third of the general diabetes population.

These insights stress the need to act differently to support different communities. We’ll be using them to create new content to support families, friends and colleagues of people with diabetes, and help to help shift attitudes.

Exercise timing matters for managing type 2

We know physical activity is an important part of managing blood sugar levels in type 2 diabetes. But does the timing of activity make a difference? So far, results on this have been mixed. At DUKPC, the CODEC study team at the University of Leicester explored why there might not be a one-size-fits-all answer.

We’ve all heard the phrases early birds and night owls – some people naturally prefer mornings, while others feel more active in the afternoons or evenings. CODEC researchers wanted to see if this natural preference – known as chronotype – influences how effective physical activity is in helping people with type 2 diabetes to manage their blood sugar levels.

They tracked the activity of 1,057 people with type 2 diabetes and recorded each person’s most active 30 minutes during the morning, afternoon or evening.

The findings showed that when people increased the intensity of their activity – for example from a slow to a brisk walk – during a time that matched their natural time-of-day preference, average blood sugar levels reduced by 7.8 mmol/mol. But when people exercised at a time that didn’t align with their chronotype there was no benefit.

This suggests that personalising exercise timing – getting active when your body naturally prefers – could be a helpful new approach to managing type 2 diabetes.

Every little (bout of exercise) helps in managing type 1

Dr Russon from the University of Exeter showed how short bouts of exercise after meals could form part of the toolkit to manage blood sugar levels in type 1 diabetes.

People with type 1 diabetes use insulin to manage blood sugars. But it works slowly and often struggles to keep up with rising blood sugar levels after meals, leading to spikes.

The researchers looked at 1,875 exercise sessions, lasting 10-30 minutes, from 553 people living with type 1 diabetes. They compared blood sugar level changes just before exercise and 20 minutes after. For each person, the researchers also recorded average blood sugar changes during similar periods when they didn’t exercise.

The results showed that exercise lowered blood sugar levels by 1.74mmol/L more than resting. This suggests building in quick exercise sessions could be a simple and effective way to help people with type 1 diabetes to manage post-meal blood sugar levels.

Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge showcases pioneering research

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge took centre stage at this year’s DUKPC, uniting researchers and people living with type 1 diabetes to share the latest progress and ideas that could transform the future of type 1 treatment.

From innovating beta cell therapy to restore insulin-producing cells, to improving immunotherapy treatments to address the root cause of type 1 diabetes, researchers are making exciting strides.

We also heard from the global teams on their projects to develop next-generation insulins that could work faster and more precisely, easing the daily burden of diabetes management.

Beyond the science, Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge researchers and our Together Type 1 Young Leaders demonstrated the value and necessity of including those with type 1 diabetes in the research process.

And we heard from experts who offered the research community advice on how to make sure scientific discoveries translate into widely available treatments.

Culprits in type 2 beta cell damage

Dr Arden and her PhD student from the University of Newcastle shared the latest on their hunt for new treatments to protect insulin-producing beta cells in people with type 2 diabetes.

Scientists think that a build-up of toxic molecules may contribute to beta cells not working properly in type 2. We funded Dr Arden to investigate the key molecular players behind this.

The team studied human pancreas cells and tissue samples in the lab. They found that particular proteins, called NOX proteins, were higher in stressed beta cells and in tissue from people with type 2 diabetes, compared to those without diabetes. They also discovered that a NOX protein was linked to reduced insulin production.

The results indicate that NOX proteins could be culprits in beta cell failure in type 2 diabetes. Scientists are already developing NOX-blocking drugs to treat diabetes complications. And this research suggests these drugs could also help protect beta cells, potentially slowing the progression of type 2.

To find out more, the team will next study what happens when they alter NOX protein levels in beta cells.

The rising challenge of early-onset type 2 diabetes

Dr Shivani Misra of Imperial College London discussed the changing landscape of type 2 diabetes. Over the last 15 years the condition has been rising in people aged 20-39 years, while remaining stable in 40–49-year-olds and decreasing in those over 60.

Professor Kamlesh Khunti highlighted that this trend is particularly concerning for people of certain ethnicities and those in more deprived areas.

The reasons why type 2 is affecting people at younger ages are complex. A shifting food environment, changes to our activity levels, urbanisation and economic pressures likely interact with genetic susceptibility, making some groups more vulnerable.

But research gaps remain. Professor Khunti stressed the need for studies that test out new interventions for young people with or at risk of type 2, healthcare professional and healthcare systems to tackle the rising challenges.

Sleep could help explain the type 2-depression connection

We know that type 2 diabetes puts people at a greater risk of depression, and vice versa.

Drs Tyrrell and Bala from the University of Exeter sifted through large amounts of genetic data and analysed how different sleep habits or problems – including insomnia, sleep quality and being a morning or evening person – affected the connection between type 2 diabetes and depression.

They found that higher genetic risks of type 2 diabetes and depression were associated with insomnia, and that insomnia may partly explain why the conditions are linked.

The findings highlight the importance of a good night’s sleep for our physical and mental health. But more research is needed to understand if targeting sleep could be a useful strategy to reduce risk of type 2 or depression.

Tributes paid to Dr Young, who spearheaded the National Diabetes Audit

A special session at DUKPC paid tribute to Dr Bob Young, a true leader in diabetes care, who sadly passed away last year. Dr Young spearheaded the National Diabetes Audit (NDA), a major project that tracks how diabetes care is delivered across the UK. Colleagues and friends reflected on his extraordinary legacy.

The NDA is unique worldwide – no other country collects and uses diabetes data like the UK. Over the last 20 years, it has shown that fundamental progress has been made – people with diabetes are living healthier and longer lives. More recently, it has provided the hard evidence needed to show the transformative power of diabetes technology and push for wider access.

The NDA has also revealed inequalities and pointed to where urgent change is needed. Data shows that care and outcomes can vary based on where you live or who you are. Dr Young was passionate about turning data into action, showing that using these insights to redesign services can help to close gaps.

His contributions will continue to shape diabetes care for years to come and reminds us of the power of data.