We invest around £6.5 million into new diabetes research every single year. This research helps us to learn more about diabetes, prevent its complications and change lives. Here we dive into a brand new project that’s exploring why insulin might increase the risk of some types of cancers in people with diabetes and how we can reduce that risk.

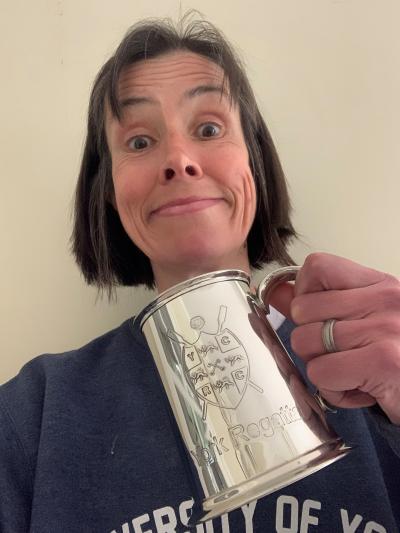

It’s being led by Nia Bryant, a Professor of Cell Biology at the University of York.

We asked her about her journey towards diabetes research. “During my PhD at the University of Edinburgh, and my first postdoctoral position (a research position that is done after a PhD) in the US, I was interested in understanding how cells are organised internally, and how this changes in response to external factors. This is an important area of cell biology. By controlling what molecules are where inside a cell at different times, cells can change their function.”

“Research into biological mechanisms this like is important to provide a solid understanding of precisely what has gone wrong in diabetes. It might not always be immediately obvious how such research can make a difference to people living with diabetes. But understanding how cells, and ultimately the human body, function at the molecular level is critically important to develop better treatments with fewer side effects,” said Prof Bryant.

One key, many locks

We know that some people with diabetes can have a small but increased risk of developing some particular types of cancer. This could be because type 2 diabetes and certain cancers have some shared risk factors, such as being overweight. But cancer risk could also be affected by one of the most common treatments for diabetes - insulin.

Cancers develop when cells in the body start to multiply out of control. Sometimes insulin can trigger this multiplying instead of bringing down blood sugar levels. People with type 1 diabetes who’ve used insulin for many years and people with type 2 diabetes who can have too much insulin in their blood, because their bodies can’t use it properly, can be more at risk of this happening. It's important to understand why this happens in much more detail, so we can stop it.

Insulin works by attaching to areas on the surface of cells called receptors, like a key going into a lock. “It was during my first postdoc that I began to read about a protein, called GLUT4, that is stored inside fat and muscle cells. When cell receptors meet insulin, GLUT4 moves to the cell surface. This helps to unlock tiny ‘doors’ in the cell membrane, letting sugar inside, and bringing blood sugar levels down,” explained Prof Bryant.

There are three main types of receptors, or locks, which are found on all cells. Sometimes though, the type of receptor that insulin attaches to can have a different effect. Instead of opening ‘doors’ to let blood sugar in, it can tell the cell to multiply. But we don’t know which type of receptor does this, leading to an increased risk of cancer. We also don’t know if GLUT4 plays a part.

In her newly funded Diabetes UK project, Prof Bryant wants to understand more about the role of GLUT4 and each type of receptor. Her team has access to several different types of man-made molecules that act like insulin, and each has been designed to only attach to a specific type of receptor. They want to measure the response of each type of receptor to each molecule. This will help them to find out which receptor brings blood sugar levels down and which one makes the cell multiply.

Opening the door to replacing insulin

In the future, this knowledge could help scientists develop new, safer treatments for people with diabetes that aren’t linked with an increased risk of cancer.

Prof Bryant explained the potential impact of her research.

“Development of insulin-like molecules capable of lowering blood sugar without causing cell division has the potential to reduce the risks to people with diabetes of developing cancer and would represent a big change in diabetes care. This research will identify such molecules, leading to new and better treatments that can be taken forward into clinical trials in the future.”

Outside of the lab

Prof Bryant told us she has more things to do in her free time than she has free time.

“I enjoy running, rowing, cycling, hiking, reading, going to the cinema and theatre. At home, I enjoy hanging out with friends and family (including our cat), and taking care of hedgehogs and garden birds (not all at the same time). And I’ve recently taken a class in ballroom dancing with my husband. Sounds like quite a lot and probably explains why I take my tea and coffee as strong as I do.”

Prof Bryant’s research could help us to find ways to better protect people from the harm diabetes can cause and bring about real improvements to treatments. Explore more of the diabetes research we’re funding across the UK.