Peter Davies

Diagnosed with type 1 aged two in 1956.

"I think it's incredibly important to celebrate the research that's been done by Diabetes UK. I've been Type 1 since I was two years old, over 60 years ago, and I'm so grateful for the changes in technology that have happened."

Peter was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes on 28 November 1956. Here he tells his story of about six decades with type 1 – from how the technology and equipment has changed, to what he’s learnt along the way.

Here's Peter talking about the impact our research has had on his life, and meeting Dr Sheila Reith, who invented the first ever insulin pen. Thanks to these breakthroughs, we're able to change lives. Help us fund more.

{"preview_thumbnail":"/s3/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/sXWFeSS15XA.jpg?itok=egQUJGOn","video_url":"https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXWFeSS15XA","settings":{"responsive":1,"width":"854","height":"480","autoplay":0},"settings_summary":["Embedded Video (Responsive)."]}

"I think it's incredibly important to celebrate the research that's been done by Diabetes UK. I've been type 1 since I was two years old, over 60 years ago, and I'm so grateful for the changes in technology that have happened."

My diagnosis

I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when I was two years and one month old. My mum regularly sent photos to my dad who was working in Kenya at the time. After seeing this photo he replied: ‘Whatever is wrong with Pete?’ – I was normally a very smiley and happy child.

My sister dug out my mum’s diary from the time, and it’s clear that the weeks and months that followed were very stressful for her, as I became more ill.

My mum's diary entries, 1956

July – Peter ill with tonsillitis - on penicillin but had dreadful mouth & tongue ulcers.

14 Aug – P still not well.

24 Nov – P still drinking lots.

25 Nov – P has been very thirsty and I am very worried about him.

26 Nov - Took P to see Dr Frankel and he has sugar in his urine. We are nearly frantic with worry. Seeing specialist on Wed. Wrote and told Robin*.

27 Nov - Very worried all day and nearly frantic. Not eating anything and P looks washed out bless him. P restless early night and frantic at 8pm I phoned Dr. P slept later.

28 Nov - Got a letter from Robin* this am. Felt awful - so worried. Saw Dr O’Reilly with P at Croydon General hospital at 2.15pm. P has diabetes and was admitted at once – an awful shock to us. We were so upset. Cabled Robin in Kenya. In such a state. Visited P at 6.30pm. P adorable but cried a lot when I went.

29 Nov - Awful day and night. My voice gone completely due to shock. Robin booked phone call to us at 1pm. Came at 2pm. What suspense. I could just speak. Lovely to hear him and he is coming home as soon as he can. Poor R, it was a shock for him to get news. Mum and I were with P from 6.30-7pm – so happy. We hated leaving him.

30 Nov – P had a little coma (first hypo) in night according to sister on phone. Mum and I saw P from 6.30 – 7pm. He had had a happy day and was so lovely – beautiful in fact. Didn’t make a fuss when we left.

(*Robin was Peter's dad who was working in Kenya).

Getting treatment

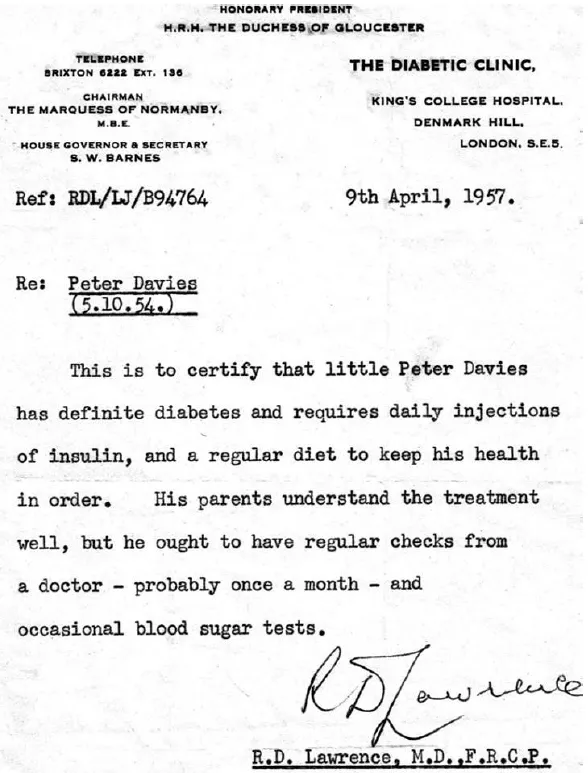

I was discharged from hospital 16 days later and was most fortunate to be referred to Dr RD Lawrence, who co-founded Diabetes UK. Dr Lawrence nearly died from type 1 himself in 1921-2, when type 1 diabetes as an outright killer. He was saved by the development of the wonder drug insulin in 1922. He devoted his life to diabetes and set up the UK's largest diabetes department at Kings College Hospital in London. I'm so lucky to still be under the care of this excellent department.

My parents were wonderful at making sure type 1 diabetes didn’t stop me from doing anything. They played such an enormous part in giving me a great start in days when so little support was available. They became real experts and always encouraged me to be independent. I remember them getting me to inject into an orange, and draw up insulin into a syringe at a very young age.

We even returned to Kenya in 1957, a few months after my diagnosis. One of my treasured letters from RD Lawrence (see below) explains my diabetes to the healthcare team in Kenya. I love the reference to ‘occasional blood sugar tests’ at the end. We do them several times each day now but used to have to wait about a week for blood sugar results to come through.

Equipment and technology

The first needles I had were used for long periods until they started to blunt, which meant they often became more painful. Some people even used to sharpen their needles. Every Saturday morning mum would boil my syringes and needles for 10 minutes and replace the methylated spirit they were kept in. We changed to surgical spirit in the late 50s, but I still hate the smell of them both!

Urine testing was the only way of having a vague idea of blood glucose levels. If the colour on the strip was blue that was considered dangerously low but was actually equivalent to anywhere between 0mm/l and 10.5 mm/l. Doctors advised to aim for green – so always above 10.5mm/l. It seems amazing now – today I do my best to aim for 5 to 8 mm/l.

(Note - blood glucose level targets are individual to each person and the target levels must be agreed between the person and their diabetes team. Find out more on the testing blood glucose levels page).

I was on two mixed insulin injections per day, which meant I had to be really rigid with my routine. If I injected at 8am, I had to eat lunch at 1pm or I’d soon have a hypo. Meals only had to be 15 or 20 minutes late for my blood glucose levels to plummet. Lots of running around and playing had the same effect. It made it very difficult to be spontaneous as a child and I had many hypos.

I still remember how much I hated having serious hypos. I hated coming round to crowds of children looking on – it was so embarrassing. I didn’t want to stand out so only told my close friends about my diabetes. They kept it to themselves and would look out for me.

When I was in my thirties during the 80s the equipment available changed significantly. For the first time, I had blood testing strips (they needed two minutes and good light to read them) and Novopens for injecting insulin. We were even encouraged to cut each test strip in half to double the number of tests we could do, to save money.

My first insulin pen was like the one pictured – discrete, stylish, easy to use and beautifully engineered. It was easily carried in a pocket and meant no more meths after more than 30 years!

In the early to mid 1990s I started using a blood glucose meter which made life so much easier and was a big step forward in keeping a record of your blood glucose control. Data could even be saved onto a PC (if you had one), which at the time felt extraordinary!

I first used a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) when I climbed Mt Kilimanjaro in 2014 with 18 other adults with type 1 diabetes. For the first time in my life I had a device to warn me of high, low or rapidly changing blood glucose levels. It would even wake me up if I was having a dangerous hypo in my sleep. It is very expensive to run though and not available through the NHS at the time (now you can get a CGM on the NHS, but it’s not available for everyone). I certainly wouldn’t be without a CGM now though, despite the cost! I have found the charity INPUT (now merged with JDRF) to be a wonderful support with information about pumps, CGMs and similar items.

In May 2015, I started using an insulin pump after approximately 85,000 injections. It is amazing technology but not perhaps the enormous improvement I was expecting. It’s quite hard being attached 24/7 but my control is so much improved compared to in my childhood days. It’s great that the CGM sensor will transmit directly to the pump and warn me if things go wrong.

Meeting other adults with type 1

Advances to equipment and technology has been life-changing and exciting for me. But so has meeting other people living with type 1 diabetes. It was climbing Mt Kilimanjaro at age 58 with 18 other adults with type 1 which changed my attitude completely. We shared the same experience and could talk easily and openly, forming immediate bonds. Before this challenge, I didn’t have any close connections with other people with type 1 diabetes. But what a difference now – I have so many close friends and contacts with the condition and we are regularly in touch.

If you have type 1, I urge you to get to know other people and families. I missed out on that support for years, and my control probably suffered as a result. I just muddled through. And when things went wrong I missed out on having someone to reassure me.

What I’ve learnt

You also have to learn to accept the condition, and to get on and make type 1 fit into your life. Take a real interest in your condition – but don’t panic when things don’t go quite to plan.

Even now, there is misunderstanding about the condition. I still have people say to me ‘You don’t look the sort’ when I tell them I have type 1 diabetes. It frustrates me, but you just have to keep educating people.

Over the 60 years I’ve had type 1 diabetes I’ve done everything I can to lead a full and exciting life – from a successful career teaching design and technology, to volunteering as a school speaker and presenter at events and conferences. I’m delighted to be involved in the planning for a new Diabetes UK Medallists group on Facebook for those who have had diabetes for over 50 years. Being able to connect online and chat about our ‘diabetes history’ is really important – even after many decades with diabetes, we can learn from each other and offer each other support. I hope that once the group has established itself, we can inspire and support others at the start of their diabetes journeys.

In June 2017, I completed the highest trek in Peru – in and around Vinicunca (the Rainbow Mountains) at altitudes of up to 5,2000m. To support my fundraising for diabetes charities go to my JustGiving page.

“Apart from raising lots of money for type 1 research, my greatest wish is that my story will offer much hope and encouragement to younger people with type 1 diabetes, their families and those who are newly diagnosed"